Rob Hudson is a Frank Trippett Advocacy and Outreach Fellow, and Community Outreach Associate for The Arc of Northern Virginia. Rob’s advocacy on behalf of his daughter, Schuyler, who has a rare disorder called polymicrogyria, has guided his personal philosophy for the past twenty years.

Growing an Inclusive World

When my wife and I made plans to travel to London this summer with my daughter Schuyler, my excitement was underscored with a low rumble of disquiet. We’ve gotten pretty good at traveling domestically; Schuyler even flies to visit her mother periodically, several states away. But I’ve never quite shaken my anxiety when she steps on that plane, because my daughter has an invisible disability. I fear what can happen because of what other people don’t know and can’t know at a glance.

The Invisible Disabilities Association writes, “an invisible disability is a physical, mental or neurological condition that is not visible from the outside, yet can limit or challenge a person’s movements, senses, or activities.” For many of our loved ones with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), having a non-visible disability can cause misunderstandings in public places, and can make it very easy for their needs to go overlooked. When traveling, that can create real problems.

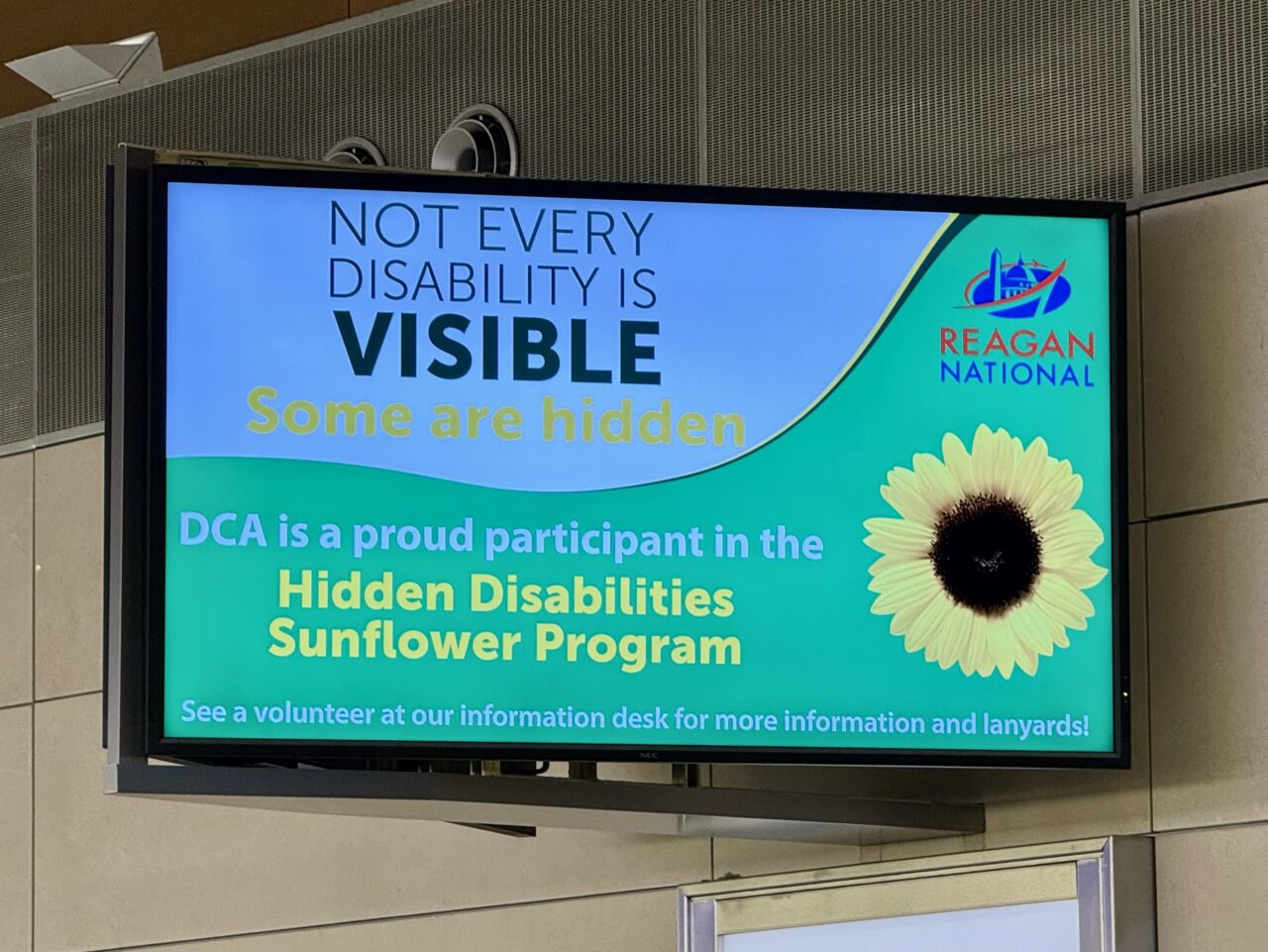

I first became aware of the Invisible Disabilities Sunflower program last year, at a travel training event hosted by our own Tech for Independent Living team. The idea is simple. Participants and their travel companions wear an accessory, like a lanyard or a pin, with a sunflower on it.

The item itself is innocuous enough; if someone doesn’t know what it means, it’s merely a fun little fashion accessory. But for those who work in public places like airports or public transportation or any other place where crowds can make travel challenging, it tells them that this person has an invisible disability, and they may need a little extra help or consideration.

I’ll be honest; I was a little skeptical, mostly because the only time I ever saw it was in the advertisements running at Reagan National Airport. But when we prepared for our trip to London, I decided we’d take all the help we could get. I went to the website and ordered lanyards for all three of us. Schuyler’s described her needs and included a photo of her. Ours identified us as her support people.

The program actually originated in the UK, and when we arrived, we were pleasantly surprised to see it everywhere at Heathrow. When we left the airport and got on the wrong train (dumb Americans, I know), the station attendants pulled us aside and made sure Schuyler was okay and didn’t need a quieter environment in which to wait while we figured things out.

The sunflower was doing its job. It was the gentlest of protectors.

Over the course of a week, we had the opportunity to see just how effective the program could be. Schuyler kept her lanyard on; we were all a little worried about being separated on the train, and knowing that people recognized the lanyard for what it represented was comforting to us. And as far as I could tell, the average person on the street or the train, never gave her a second glance. She appeared to be a pretty young lady who liked sunflowers.

But when we encountered people involved with crowd management and infrastructure, the sunflower quietly made a difference.

At the Tower of London, the woman taking our tickets cheerfully greeted Schuyler and gave her a wristband, adorned with the same green background and sunflowers. She said that when we reached lines for high traffic places like the crown jewels, the sunflower would allow her to bypass crowded lines. (She said queues, of course.) When we returned to Heathrow for our return flight home, we encountered special lines at security that allowed bearers of the sunflower a quicker path through.

It wasn’t just the sunflower, either. On public transportation like buses and trains, we were inundated with ads from the Mayor of London’s office. “Be considerate to others,” they said. “Please remember, not all disability is visible.”